Rod Kersh graduated from Dundee University in 1989 and has been working as a geriatrician in South Yorkshire for the past twelve years. Most recently he has moved out of acute care to support a new model of community geriatrics divided between a community role delivered by Rotherham NHS FT and as physician-partner at Manor Field Surgery, a GP practice in Rotherham. Rod blogs at www.almondemotion.com and he is @RodKersh on Twitter.

In my experience I have found three types of doctors; Those who work very fast, very slow or somewhere in the middle. This is obvious and logical as human behaviour is divided on the basis of a normal distribution, with most being average.

In life, there are those who work and act quickly; my mum would say, ‘chick-chak’ which I think is a derivation of Hebrew meaning, ‘promptly, without messing about,’ and, those who tend to dilly-dally.

I remember when, as a junior doctor working in A&E, they had a top-ten of patients seen in the six-month period of the rotation. Some colleagues would plough through the numbers, others would move more methodically. The NHS being what it was and is, would usually reward those working at the fastest pace, seeing the most.

I know doctors who carry tremendous workloads, seeing two, if not three times as many patients in a year as colleagues.

Again, this person would be considered the ‘workhorse’ of the team and duly valued/appreciated/praised.

I will not say where I come into this mix, although I believe I am somewhere in the upper percentile, that is, not the fastest, but quicker than average.

Now, the question, is, whether the super-fast doctor is more efficient and effective than the slower-one? Is the latter more meticulous, does the former miss more than they realise?

This is the crux of this blog.

Should we all work more quickly, potentially, superficially or is slowing-down preferable?

The NHS, like any health system in the world today is constrained by finite resources, with the most valuable being staff. Surely, we would want our staff to be as productive as possible – plough faster?

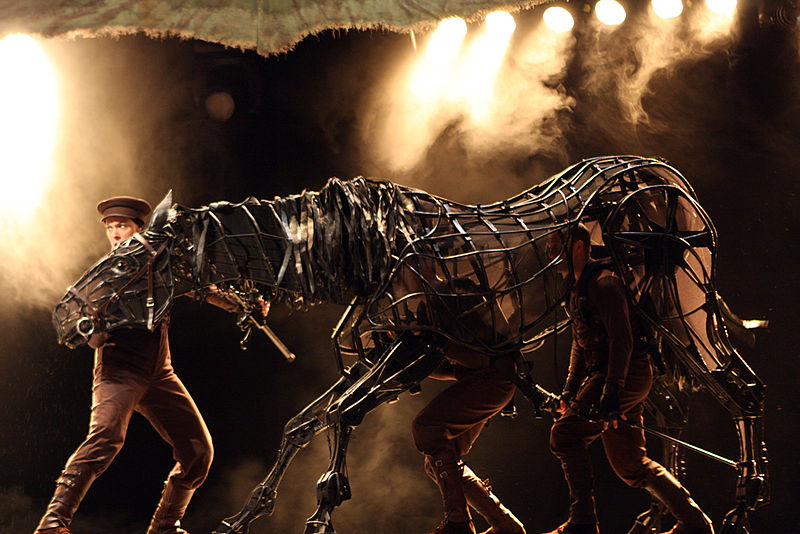

The image, from Michael Morpurgo’s War Horse, where Joey is pitted against the tractor comes to mind.

You could potentially measure some of this, although the inherent risk of doing so would be to introduce targets – each doctor should see ten patients an hour, or something like that; all with the realisation that no patient is the same, each have different needs and conditions – a viral-rash versus learning you might have cancer being two extremes.

Some doctors manage to negotiate this process by excluding their own emotions; dealing, if not in a formulaic manner, at least, by the book. Test-Investigation-Diagnosis.

Using this logic, robots would probably out-perform humans.

Yet, do we want robot diagnosticians?

Is it the prescription that ends the consultation, what matters or how the patient and the doctor feel?

Should feelings come into it?

Part of this reflection relates to something I have experienced since moving out of the hospital.

I am almost certainly ‘seeing’ fewer patients, and, my encounters are longer. My innermost feeling is that these are deeper, more meaningful and effective experiences, hopefully reflecting patient outcomes, although I don’t have any evidence to support this.

In many instances, I am seeing people who cannot get out of their houses to attend either the surgery or the hospital; those confined to bed, or who are too frail or vulnerable to leave their home.

Mostly they would be regarded by the traditional, that is, the hospital system as ‘DNA’s’ – Did Not Attend’s.

In the world of paediatrics, if a child DNA’s an appointment, there is an investigation to determine why.

In adults, DNA is usually accompanied by a letter to the GP saying, ‘Your patient failed to attend their appointment, if you wish them to be seen, please re-refer’ or similar.

I remember a few years ago trying to apply the same children policy to vulnerable adults, although I am not aware of this having taken-hold anywhere.

So, I see fewer patients, yet my relationship with them is deeper – my insight into their lives more profound also; where they live, their state of accommodation; are they in bed, do they get dressed, smoke, have visitors, carers, a cat or dog?

For the first time in my career, last week, I sat in a patient’s living room as two carers hoist-transferred him from bed to specialist chair. We talked about his conti-pads, aches and pains, hopes for the future.

This all adds richness to my perception.

And this, I feel is most likely the question.

For, I feel I am seeing a reasonable number of people when I travel round the houses – a new patient taking approximately 40 minutes to review, with more reliance on phone-call follow-up and a higher rate of discharge than would happen in a hospital clinic (where never-ending ‘see you in six-months’ is sometimes the routine).

In my primary care role, I am able to (mostly) stop medicines directly at the source, although sometimes I do prescribe the odd painkiller or blood-pressure treatment; I am able to cancel clinic visits that the patient doesn’t want and will not add value. I can look into different computer systems and save repeat blood tests and x-rays that haven’t crossed the NHS silos.

I go as fast as I can; writing notes with the patient in the room; touch-typing as I am doing now. The electronic nuggets of patient data sieved-off for analysis somewhere remote.

In an ideal world, GP appointments would be longer than 10 minutes (some places practice five-minute reviews, which is difficult to conceive) – we would have as long as the patient and doctor require to cover what is needed; assessment would be thorough and holistic.

For older people, who are my focus, there is evidence to support this style of practice, it is (somewhat frustratingly) called, ‘Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment’ – or, CGA; this is a holistic review of a patient’s needs.

(Let’s start calling it ‘Comprehensive Review of Older People’)

I take into account falls, nutrition, continence, medicines, relationships, social isolation and end of life planning; it covers all that might be relevant and, over the years it has been demonstrated as the most effective way to support older people in the community – reducing falls, hospital admission, deterioration, move to residential or nursing care and death.

In recent years there has been an expansion in how this assessment is completed and by whom.

Part of the point is that this cannot be completed in five, ten or even 20 minutes.

If you want to examine the many different aspects of life and care that affect an individual you have to go deep, and, this is something that you can’t do quickly, no matter your working style.

You can conceive robots/computer programmes that are able to detect subtle changes in heart, respiration rate and perspiration, allowing human-type pauses between questions, although I pray this is a long-way off.

I doubt you can change the innate behaviour of individuals to the extent that those who work fast can entirely slow-down, nor can those who are slow speed-up, although there are probably lessons to be learned from both ends of the spectrum.

Would I want a tractor doctor or a Joey?

I guess this would depend on the circumstances.

If I am bleeding out from a ruptured aneurysm, bring-on the fastest, most up-to-date Artificial-Intelligence powered tractor/plough.

If I am lonely, off my food, worried, recovering from a nasty infection or repeatedly falling, bring me Joey.

You can find the blog on my site here - www.almondemotion.com/2019/08/21/doctoring-fast-and-slow/