The following chapter of this guide provides a reference guide to care and support planning for primary care and community clinicians, with emphasis on the care of older people living with frailty. It explains what personalised care and support planning is, the recommended components, tips for developing a Care Plan, with a list of resources to help clinicians and patients engage in personalised care planning.

What is care and support planning?

The Royal College of General Practitioners defines personalised care and support planning as:

“A powerful way of creating an environment which helps clinicians to support self-management by patients of their own long term condition.”

However a more holistic definition comes from the new NHS England Service Component Handbook on personalised care and support planning:

‘Personalised’ care and support planning is an essential gateway to better supporting people living with long term physical and mental health conditions, and carers, helping them to “develop the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their own health, care and wellbeing.” It helps individuals and their health and care professionals have more productive conversations, focused on what matters most to that individual.

The term ‘personalised’ reflects that the “conversation relies on equal input from the individual and their carer, where appropriate, alongside health and care practitioner(s)” and looks at the individual’s health and care needs within the wider context of their lives. ‘Care and support’ signals that “people need more than medicine or clinical treatments and that social, psychological needs and support to do things for themselves are equally important,” alongside opportunities for community inclusion and support.

The essence of personalised care and support planning is:

- A conversation between an individual (including their family/carer when appropriate) to discuss life priorities, consider options and agree goals.

- Working with the individual to identify the best clinical treatments and/ or social and psychological support for them, taking account of their life priorities and the agreed goals.

- Agreeing the actions individuals themselves will take to help them achieve their jointly agreed goals and the support they may need to do that.

- Recording the conversation in a way relevant to the individual.

- A planned and continuous process, not a one-off event.

There is a drive for care plans to be more widely implemented; the NHS Mandate included a commitment that by April 2015:

“Everyone with long-term conditions, including people with mental health problems, will be offered a personalised care plan that reflects their preferences and agreed decisions.”

The NICE Guidance for Older People with Multi Morbidity published in September 2016 recommends a care plan reviewed annually.

Why is it vital?

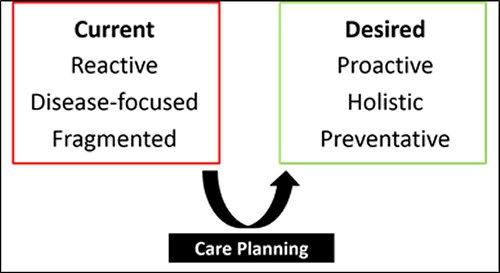

One of the most important challenges facing the 21st century NHS is the need to improve the treatment and management of long-term conditions, multi-morbidity and support and care for older people living with frailty. Part of the problem relates to how our models of care tend to be structured. Traditional models of care, which focus on the management of single long term conditions, do not fit the paradigm of care required for those living with multi-morbidity and frailty. It is recognised that change is needed. The term ‘house of care’ has been adopted as a central metaphor in NHS England’s plans for improving care for people with long-term conditions - care planning has been recognised as being at the very heart of this process of driving change (Figure 1, below).

In an age of austerity, it is worth noting that evidence suggests personalised care and support planning can produce the most appropriate use of limited healthcare resources.

What should a care plan include?

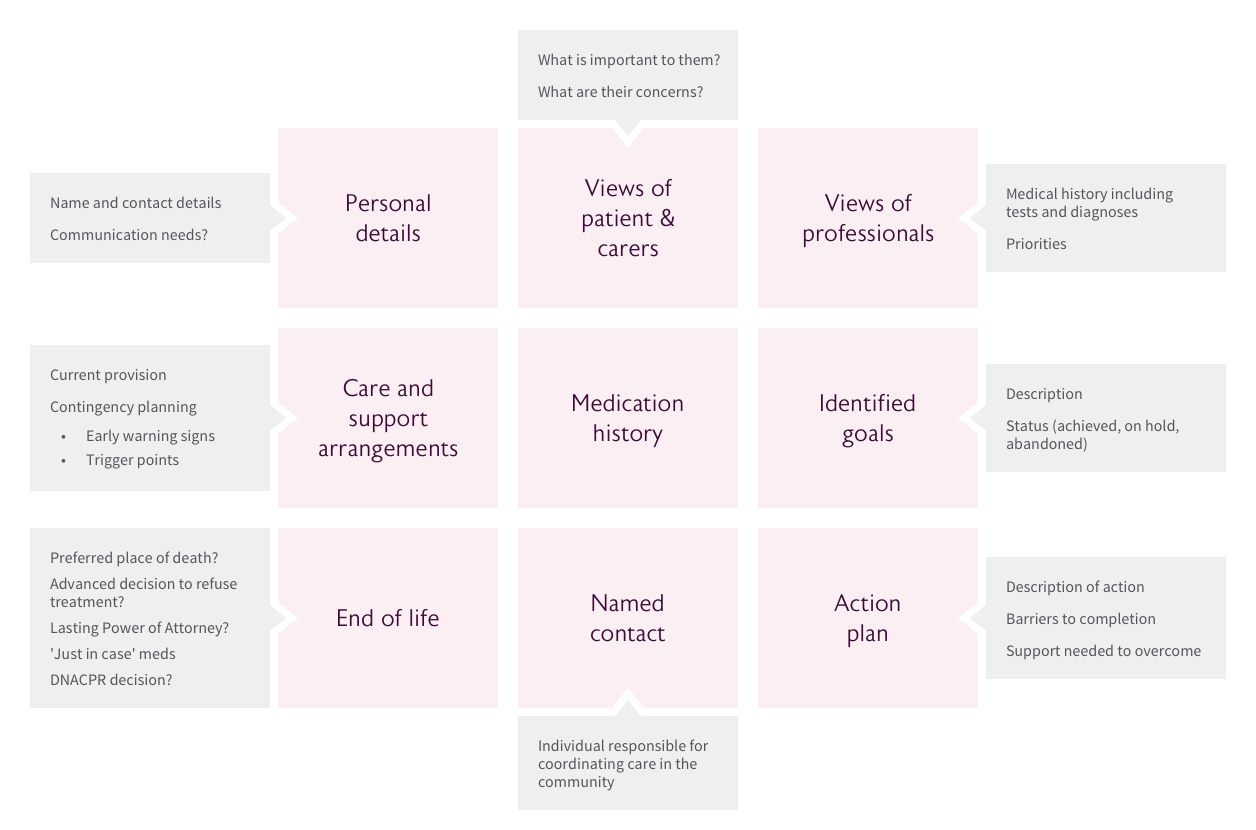

The diagram below summarises nine key areas that ought to be included within a care plan for a frail older person.

Key steps to developing an effective care plan

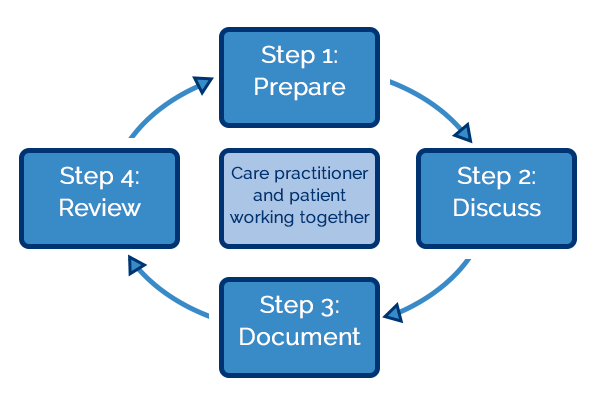

Figure 2 displays four steps to developing a care plan that are identified in the National Voices Guide to Care and support planning.

It is critical to highlight that, despite the simplicity of the diagram, this process should be both collaborative and continuous. Furthermore, it is not intended to be prescriptive, but to stimulate thinking.

Goal setting and action planning

It is important to emphasise that care planning is much more than solely preparing for when a patient’s condition deteriorates. A more pro-active, positivist outlook on care planning is to consider care plans as a way of empowering patients to maintain or improve their health - central to this process is goal setting. Traditionally, goal setting has tended to remain within the medical paradigm; that is the goals themselves have tended to focus on treatments, medications or test results. Effective care plans, that improve health and well-being, require goals that are based on patients' personal targets and should link to functional outcomes that they want to achieve.

Two contrasting examples of goal setting are shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: An example of goal setting and action planning for a patient with recurrent falls (adapted from Personalised care and support planning handbook, Coalition for Collaborative Care):

| Instead of | The plan should read |

|

Need: Fall prevention Goal: Prevent A&E attendances Action: Attend physiotherapy appointments once per month |

Need: I need to build up my muscle strength to assist with balance Goal: To be able to use the stairs without needing any assistance Actions: Doctor to refer me to a physiotherapist; I will discuss strengthening |

Goal setting in this manner has a number of advantages, particularly in the context of older patients living with frailty. Firstly, it encourages patients to articulate what matters to them and thus drives more patient-centred care. Secondly, this approach can help to simplify decision-making in patients with multiple morbidities by focussing on outcomes that span conditions and aligning treatments toward common goals.

It is also important to recognise that in the context of frailty, by definition, things can change or take a turn for the worst. The care and support plan might usefully include pointers for an individual and their carers as to what action to take if this happens so as to avoid further rapid deterioration, reduced function and ultimately loss of independence. This Escalation plan could range from a very medical issue, such as what action to take if weight is gained rapidly (suggesting fluid retention and deteriorating heart failure), to a problem with care (‘What should I do if the carers haven’t turned up?’) or to a more personal issue (‘What I should do if I don’t feel well enough to go to the exercise class?’). Giving individuals support in considering these possibilities can lead to an increased sense of control and confidence in the support structures.

A care and support plan for an individual living with frailty should also include the actions which the individual might wish to be taken in the event of a crisis such as a fall, an intercurrent illness or any other situation where an ambulance or out-of-hours doctor might be called. This Emergency Care plan or Urgent Care plan will document what the professional and the individual have discussed is probably right for that person in the event of a crisis. Of course it is not always possible to predict exactly what will be needed, but thinking about whether hospital admission is appropriate after they have fallen, or whether the patient would rather be at home if they had a life threatening illness, in advance of the situation will provide valuable guidance to the emergency health professionals at the time of the crisis. It also helps to document the individual’s usual observations if they might be relevant to the issue. For example, someone with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who has persistently low blood pressure and who has falls is more likely to be taken into hospital unnecessarily (and to their detriment) after a fall, if the ambulance crew are not aware that a systolic BP of 90mmHg is normal for that individual.

Tips for goal setting

Drawing on the mnemonic ‘SMART’ may result in more effective goal setting:

- Specific: both the goal and the action plan (which must be explicit - who will do what and when?).

- Measurable: consider how we can help people to track whether they are achieving their goals (Diary? Checklist?)

- Achievable: Patients and clinicians must ensure that goals remain within the realms of achievability given the patient’s clinical situation. To assess this, it is worth asking patients to grade their confidence in achieving their aim using a scale of 1 -10.

- Relevant: to the patient and their situation.

- Timely - as in, is it possible to make a difference in a relevant time frame and when should things be reviewed?

Involve carers and family (when relevant) with these discussions, since they can play a significant role in this process:

- They can help with the construction of achievable goals.

- They may be an active participant within the required actions.

- They may be required to help provide ongoing motivational support to the patient.

Further reading

I’d like to see a downloadable example of a care plan [temporarily unavailable].

I want to read a bit more about goal setting and action planning:

Why? Reuben, DB. & Tinetti ME (New England Journal of Medicine 2012; 366:777-779).

I’d like to read about a real-life example of how a general practice has gone about implementing this process systematically: The Holmside Story.

I’d like to read about how a general practice has worked in partnership with the Voluntary sector to put people at the centre of what they want to do, enabling them to live the life they want to live, whilst improving health and care outcomes using personalised care and support planning: The Cornwall Link [temporarily unavailable].

I’m interested in hearing a bit more from GPs reflecting on their experiences of implementing care planning: 8 minute YouTube video.

I'd like to see the recent BGS/RCGP Guidance on Integrated Care.

**Resource developed by ‘National Voices’: a coalition of health and social care charities, who worked with a wide range of services users, to develop a patient-centred guide to care planning.