This publication outlines how to deliver proactive care against core components and key enablers, acting as a roadmap for implementing the NHS England framework and delivering proactive care services. This chapter goes into greater depth about the five core components and three key enablers for delivery.

Proactive care services often start from different places. Some have started from a system wide prioritisation of proactive care with senior leadership support and dedicated funding. Others have started from the enthusiasm of individual clinicians at Trust, PCN/PCC or practice level. The way that services are set up will be dependent on geography, available funding, infrastructure, and workforce.

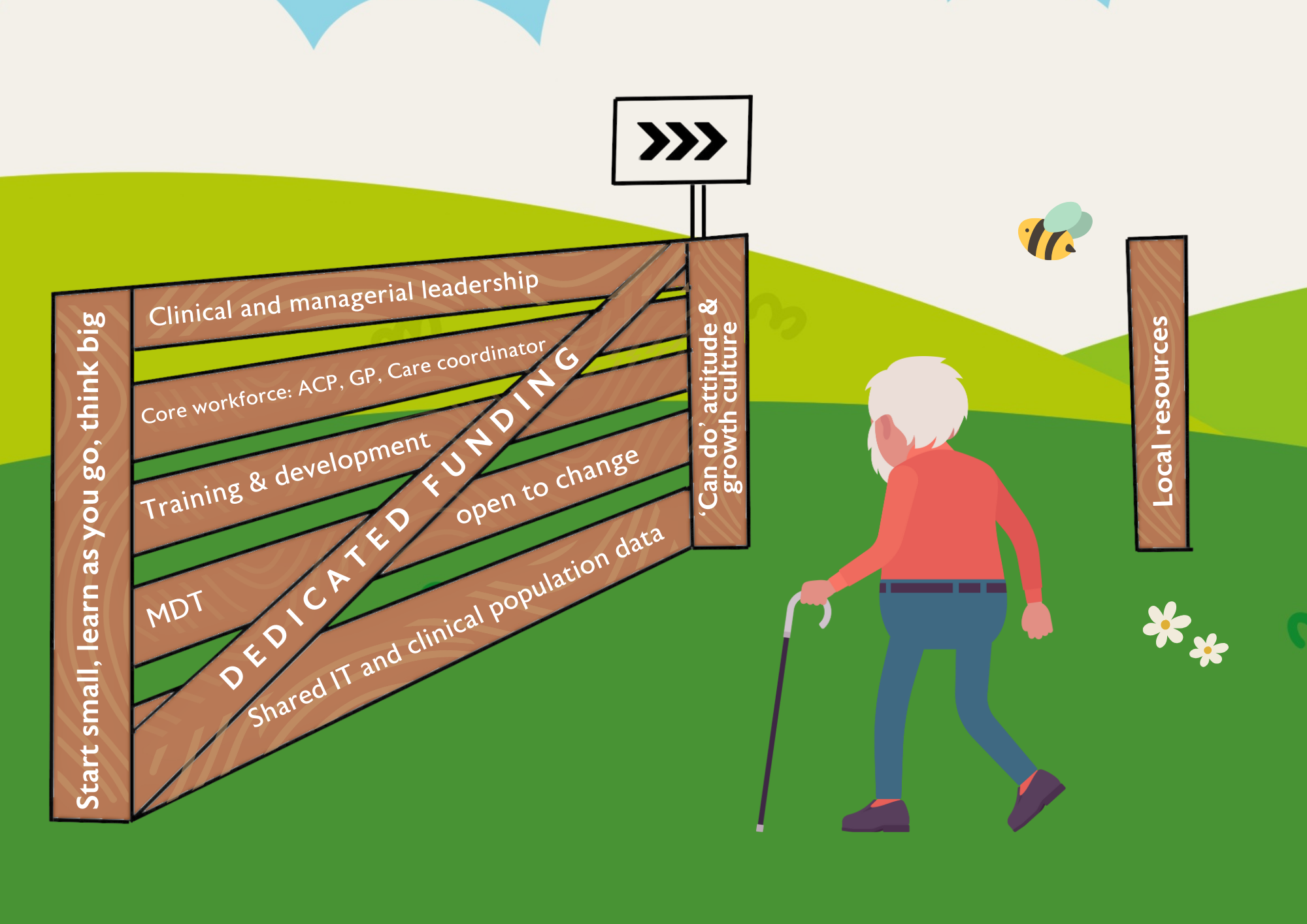

Advice from healthcare professionals who have set up proactive care services is to “Start Small Think Big,” and to “Start from where you are”. Whatever the starting point, there are some key steps to setting up a proactive care service that can be applied to all proactive care services in primary and community care settings. Following the five core components and three key enablers outlined in NHS England’s proactive care guidance, this chapter outlines how to deliver proactive care services for older people living with frailty.

Core component one: Case identification

Identify the cohort the service will focus on and develop an approach for case identification

Most services initially focus on older people with moderate and severe frailty living in their own home. People with mild frailty and complex health and care problems will also benefit from the care co-ordination provided by proactive care services, with some services including them in their cohort. Areas with high levels of deprivation may have higher levels of younger people with frailty and therefore may choose to lower the age for the service. As the service develops, the cohort it supports may expand to include different criteria such as older people with stroke, dementia, brain injury and chronic neurological conditions including Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis.

Proactive care services can use a wide range of different approaches to identify people suitable for interventions. This can be as simple as looking at admission and discharge information or as complex as using algorithms to identify people from system data.

The electronic frailty index (eFI) is a tool that uses data from a patient’s electronic health record to identify and grade the severity of frailty. Data reports using eFI alone can be used but they often produce large lists of people, some of whom may not have frailty. Therefore, BGS members recommend using eFI with other criteria to improve accuracy.

Data report criteria options include:

- System-wide data reports

- Moderate frailty + multiple long-term conditions (LTCs)

- Moderate frailty + severe polypharmacy and/or high-risk medication prescription (e.g antipsychotics)

- Moderate and severe frailty + no GP encounter in 6 months

- Older people using multiple services

- locally defined cohorts based on social deprivation and other factors (e.g. hospital admissions or readmission frequency)

PCN/ PCC and practice level data reports

- Frailty + Parkinson’s disease

- Frailty + depression and anxiety

- Frailty + no GP contact for over a year

- Frailty + increasing home visit requests

- Over 75 and not on a chronic disease register

The data reports generate valuable lists, but a human is often needed to screen the lists to find appropriate individuals. Services use a variety of different ways to screen the lists. Options include reviewing practice records, sending out a questionnaire asking about frailty markers, and telephoning patients and carrying out a telephone assessment based on frailty markers.

The second version of the eFI (eFI2) may provide better discrimination of frailty and risk of adverse outcomes; if this is confirmed on publication, this will be a very valuable addition to risk stratification tools. The eFI2 has been registered with the MHRA as a Class 1 Medical Device and will be made nationally available through implementation into primary care electronic health record systems and can also be provided directly to ICBs and PCN teams as needed.

Other services’ caseloads or waiting lists can be used to identify suitable people, such as community matron caseloads, adult social care waiting lists, and adult community occupational therapy waiting lists. Some services also find suitable patients through referrals from health and care professionals rather than data sources. This may be more effective in established services once professionals are aware of the service, its aims, and impact. BGS members recommend promoting the service and encouraging the multidisciplinary team to use their own judgement to identify older people who would benefit from a comprehensive health and care review and personalised care plan.

The eFI and other risk stratification tools are not clinical diagnostic tools; they are tools which identify groups of people who are likely to be living with varying degrees of frailty. Therefore, when an individual is identified who may be living with frailty, direct clinical assessment and judgement should be applied to confirm a diagnosis. The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is used by most services to identify people for proactive care interventions. CFS is used to screen people on lists produced by data reports and is used as a basis for referrals. It is advised that each service trains health and care staff to ensure they understand the CFS and how to use it.

Most services use a range of methods to find suitable people with data reports being used to identify people initially and referrals identifying more people as the service becomes more established. Decide how your service will initially find, screen and assess suitable patients, but be willing to be flexible and adapt your process as the service develops.

Core component two: Holistic assessment

Agree the process for delivering holistic assessments, such as CGA

Consider which member of the core proactive care team will be carrying out the Comprehensive Geriatrics Assessment (CGA) and where this will take place. In most services, the initial assessment is carried out by an ACP with support from a Care Co-ordinator. Initial assessments can be carried out in a range of settings such as community clinics, GP surgeries and the patient’s own home. People with mild or moderate frailty are more likely to be seen in a clinic or GP practice and people with severe frailty are usually seen at home.

Home visits provide useful information about the patient’s home environment that cannot be seen in a clinic, but they can be time consuming and expensive. Limited access to rooms in community clinics and GP practices, compounded by poor access to transport means that some people who could attend a clinic are unable to do so. This increases the number of home visits and reduces the number of assessments that can be carried out by the service. In some areas, free transport schemes are available to bring patients to community clinics and GP surgeries, such as the Good Neighbour scheme. One practice-based service that used a Good Neighbour scheme enabled 70% of people with moderate or severe frailty to attend. Services should source rooms in GP surgeries and community clinics and free transport, if possible, to increase the service capacity.

When designing the service, the format of initial holistic assessments should be agreed. A holistic assessment should include physical assessment, functional, social and environmental assessment, psychological components and a medication review. The Geriatric 5Ms framework includes five areas of focus: mind/mentation, mobility, medications, multicomplexity, and what matters most, and can be a good framework for a holistic assessment.4 Services should include family and informal carers in the assessment if appropriate.

Most services use an electronic template for the CGA, and this should be set up before the service starts seeing patients. Training for staff on using the template should be provided to ensure consistency.

Core component three: Personalised care and support planning

Develop an approach to personalised care and support plans

Services should develop a format for a personalised care and support plans. This can be anything from a discussion with the patient and their carer to a detailed document that is shared with the patient, GP practice, and other services involved in their care. Key aspects of the plan usually focus on falls prevention including strength and balance training, nutrition advice, social care support, medication reviews, advance care planning and emergency care plans such as ReSPECT forms. The plan should include preventative strategies to address common issues associated with frailty. This includes vaccinations, regular screening (e.g., for osteoporosis), and proactive management of chronic conditions. It is important to also consider lifestyle modifications such as physical activity, balanced nutrition, and social engagement.

A process for sharing the CGA and personalised care and support plan with other organisations should be developed. This is particularly important for advance care plans, Treatment Escalation Plans and ReSPECT forms.

Involve family and caregivers

Involving and supporting family and caregivers in the care process is an important consideration. Provide education on frailty management, coping strategies, and resources available. Engaging caregivers helps in ensuring that the patient’s needs are met and can improve overall care outcomes.

Core component four: Co-ordinated and multi-professional working

Promote proactive care and engage senior leader support

It is important to identify and engage the support of senior stakeholders with the funding and power to prioritise the development of the proactive care service. Depending on your location in the UK, this might be your local Integrated Care Board, Health and Social Care Partnership, Health Board, Health and Social Care Board, Trust leaders, PCN Clinical Director, Primary Care Cluster or GP Partners in a GP Practice. With the current lack of funding of proactive care across the UK, this may be a challenge but tools such as BGS’s Be proactive: Evidence supporting proactive care for older people with frailty can be used to make a business case.3 Support your case by sharing evidence that proactive care works, share patient stories of substandard care where proactive care would have made a difference, and stories of how proactive care has reduced duplication and fragmentation of services. The case studies in this document alongside BGS’s evidence publication can help build the case.

Identify and support proactive care leaders

Effective implementation of proactive care depends on motivated leaders with a vision, and this should be factored into funding requirements. Identify the leaders for the service at the start and ensure that they are supported with protected time and training opportunities. Both clinical and managerial leadership is beneficial but in smaller services, clinical leaders may do the job of both. Leaders should be provided with training in negotiating skills, service development, and project management. Providing networking opportunities can help leaders to share new ideas and provide mutual support.

Agree proactive care team membership for service

Core team membership

At a minimum, the core proactive care team should consist of a GP with an interest in frailty, an Advanced Clinical Practitioner, and a Care Co-ordinator. If the resource is available, a gold standard core team can include professionals from mental health services, pharmacy, social care, therapy and geriatric medicine. Core team membership will vary depending on whether there are funded roles available, if there is protected time for existing staff, the size and demographic of the population, funding, and local resources.

Advanced Clinical Practitioners

The core team should include highly trained professionals who are able to manage a complex caseload, such as ACPs from either nursing or allied health professions. It is more important that they have the right mindset rather than belonging to a specific profession as generic skills for managing people with frailty can be acquired. Availability of highly trained experienced staff is limited so staff should be offered training and support on the job if needed.

Care Co-ordinators

Care Co-ordinators are non-clinical staff who help to Co-ordinate and navigate care across the health and care system. They are vital members of the core team, providing support to reduce the fragmentation between health and social care. A key part of the role is forming relationships with patients, carers and families to help improve the continuity of care by acting as a connector between health and care teams. They are often the main link in the MDT to social care services, local authority services, and voluntary organisations. They can provide skilled administrative support for the core team by reviewing day to day referrals and hospital discharges and flagging up patients suitable for the proactive care service. In some teams, the Care Co-ordinators help to identify cases by reviewing lists of people identified via data reports and phoning patients at home to assess their degree of frailty. They can also help to promote the proactive care service to external organisations.

GPs

GPs are crucial members of the core proactive care service team, contributing medical knowledge and acting as a link between general practice and other services. Some GPs are employed by community services and acute trusts to work in proactive care, while others are employed directly by PCNs/PCCs or equivalents and general practices. In some smaller proactive care services, GPs are given dedicated protected time within their existing role to work for the proactive care service. Funding is often a barrier for GPs wishing to work in proactive care.

Administrative services

Administrative support can release clinical time and is often overlooked. Larger services require in-house administrative support while smaller services may need to rely on administrative support from the community services, PCNs/PCCs and GP practices where they work.

Agree the infrastructure required for the proactive care service

Employment

The core team can be employed by a community or acute trust, a PCN/PCC or equivalent, a general practice or a combination of any of these. As long as the service can function as one team, the employing organisation is not important. Where line management arrangements are outside the core team, it is important that the line manager has an understanding of frailty and the aims of the proactive care team.

Core team location

It is important that all core team members have a shared base where they can meet up on a daily basis. It is helpful if the core team is co-located with the community teams, allowing collective responsibility, open conversations, reflection and debriefing. It also makes it easier for MDT members, such as geriatricians, who may only be available once a week to be part of the team. However, although helpful, co-location with community services is not essential. Some PCN/PCCs and practice led services are co-located in GP surgeries allowing close communication with other practice based multidisciplinary team members.

Service hours and cover

Proactive care services usually operate standard working hours as they do not generally deliver an urgent response. Some services offer an urgent response during working hours for people known to them who have fallen or need urgent support at home, but this is not usual practice. Smaller proactive services often do not have arrangements for cross cover for holidays or sick leave and work is left for the clinician to pick up when they come back to work. Services with larger core teams have enough staff to cross cover so can provide a full service within their standard operating hours. It is important to consider how the work will be covered when staff members are on leave or sick.

Supervision and mentoring

Access to supervision and mentoring for core team members is advisable and should be set up at the start of the service.

Recruit the core team

Before starting the recruitment process, consider not just the experience and skills of the person but also their key principles. Ensure that the job descriptions and advertisements are adapted accordingly.

This may include the following key principles:

- Share the core values of what you want to deliver

- Are team players who are committed to the purpose of the whole team, not just their own function

- Are diverse (this will bring greater breadth to the team)

- Keen to develop professionally

- Can work autonomously

Create a local induction and training package for new workers joining the team, which includes becoming familiar with:

- The values and goals of the proactive care service

- Each other (can include team building exercises)

- The venue and the area they will be working in

- The multi-professional team they will be working with

- Skills required and specific areas of training such as coaching, leading MDTs, compassionate leadership, and IT skills

- It may also involve shadowing a neighbouring proactive care team, if available.

Set up regular MDT meetings at practice or PCN/PCC or equivalent level

Regular multidisciplinary meetings are key to ensuring that the necessary multidisciplinary interventions are delivered. They provide dedicated time to review patients as a team, have case discussions, establish clear and simple referral pathways, and help members to get to know each other. MDT meetings can be face to face or virtual or a combination of both. Virtual meetings help some members to attend but may impede team building, informal information sharing and learning. A stable team with regular attendance by the same people helps to establish and maintain effective team working.

MDT meetings should be set up for each PCN/PCC, and at practice level as well if preferred. As well as the core team, MDT meetings should include a community matron, community nurse, a social worker, a mental health professional, a PCN/practice pharmacist and a geriatrician (if available) as a minimum. Other services attending MDT meetings can include intermediate care and community rehabilitation teams.

Promote the service

Proactive care is a new concept for many health and care professionals, requiring a change in culture and heavy promotion. For bigger services, a system-wide promotion exercise may be needed, aimed at health and care professionals, the local authority, voluntary organisations and the wider public. For smaller services, promotion to local referrers may be sufficient. It can take time to build up referrals so if the service is struggling to get numbers, keep the referral process simple, do not reject referrals, and spread the word.

Launch the service

Launch the proactive care service when the induction is fully complete, not before. Consider a mini proactive care service, such as in one general practice, for the first eight weeks while ensuring that everything is in place. This will allow time to refine any processes and make sure that the core team is confident in their roles. If everything is going well, roll out the function earlier than eight weeks. Provide regular supervision for all team members and keep an eye on how the service is developing so that any issues can be managed promptly.

Core component five: Continuity of care

Provide a clear plan for continuity of care, including an agreed schedule of follow-ups

A holistic assessment or CGA and personalised care plan is of no value if the plan is not implemented. Follow-up is required to ensure that suggested interventions have been put in place. This may include ensuring that a referral to social care has been received and a social care package organised if needed, the medication has been changed, the home adaptations have been put in place, and the patient has been able to attend the strength and balance training. Part of the core team’s function is to liaise with other services and follow up to ensure that multidisciplinary interventions have taken place and review how the patient condition has changed over time. It is important to recognise that frailty is not a static condition and follow up is essential in ensuring that interventions are working.

Involve and support family members and caregivers in the care process if appropriate. Provide education on frailty management, coping strategies, and resources available. Engaging family and caregivers helps to ensure that the patient’s needs are met and can improve overall care outcomes.

Enabler one: Flexible workforce

Ensure the service is sufficiently resourced

A flexible multidisciplinary workforce, working across organisational boundaries is central to the delivery of proactive care. The service needs to be sufficiently staffed, with a minimum core proactive care team consisting of one GP, one ACP, and one Care Co-ordinator. As outlined, this can expand to professionals from mental health services, pharmacy, social care, therapy and geriatric medicine if the resource is available.

Ensure training and development needs are met

The proactive care team will need to be supported through training opportunities to ensure that they have the necessary skills to care for older people with frailty, and to work across organisational boundaries. Meeting the training and development needs of the core team will not only enhance the skills of the team, but support recruitment and retention. All MDT members require an understanding of frailty and knowledge of frailty syndromes such as falls, immobility, delirium, incontinence and side effects of medication. The NHS document The Frailty Framework of Core Capabilities outlines the core capabilities for health and care staff working with older people with frailty.30 Training resources include the BGS’s frailty elearning course which covers the identification of frailty and interventions to improve outcomes for those with frailty. 31 Communication skills training is also important for all MDT members to work across cross organisational boundaries. Other useful training areas for ACPs in particular include:

- Advanced communication skills.

- Advance care planning and completion of Treatment Escalation Plans and ReSPECT forms.

- Common mental health problems and use of screening tools for anxiety and depression.

- Diagnosis and management of dementia and delirium.

- For GPs, the recently published RCGP GPwER in frailty framework offers a benchmark and recommendations for professional development and progression within this role.32 It covers how and where care is delivered, services that interface the role, and to how to develop and maintain the role. Access to a geriatrician and psychiatrist for older adults for clinical advice is valuable to enhance skills in medical management of older people but not essential.

Multidisciplinary team working and mentorship with a doctor helps non-medical team members to enhance their medical knowledge and aids understanding of diagnosis and prognosis which are key factors in management of older people with frailty. Access to a community geriatrician and a social worker can help the team work through complex situations.

Develop a shared proactive care workforce plan at service level

To ensure the proactive care team is supported with the appropriate staff resource, training opportunities, and ways of working, new services should create a shared workforce plan between partner organisations outlining how the service will work. This should outline members of the proactive care team, methods of cross-organisational working, and training requirements.

Enabler two: Shared care record

Ensure the proactive care team has access to shared care records

Information sharing is vital for proactive care services as it requires multidisciplinary interventions across a range of health and care organisations. If possible, ensure that core team members have access to all electronic patient records, including general practice, community services, hospitals and social care. If this is not possible, ensure that they have access to all the shared records available in the area.

Enabler three: Clear accountability and shared decision making

Establish clarity on the aim of the service and develop shared values

Spend time during the development of the proactive care service with local leaders to agree the aim of the service and develop shared values. Common aims of proactive services for older people with frailty include:

- Improve care for people with frailty.

- Bring together a team to deliver effective services for older people with frailty.

- Improve communication between the organisations looking after the patients.

- Reduce fragmented care and duplication.

- Reduce higher cost work which is unable to fully meet the need of the person.

- Improve job satisfaction of those providing care

For older people with frailty, providing the holistic care they require within the community can be challenging. Holistic care often consists of many overlapping services such as physical health, mental health, psychological services and social services as well as community and voluntary care services. Multidisciplinary community team working enables the right person to look after the patient at the right time and place. Therefore, it is important that the teams share the same values of delivering patient centred care around what matters most to people and working together to provide the best quality care for patients. Time spent on discussing the aim of the service and how leaders will work together helps to ensure the service runs as smoothly as possible and will minimise conflict in the future.

Agree a process for data collection and evaluation

Data collection and outcome measures should be agreed when developing the service. It is possible to measure the reduction in hospital admissions and the length of stay, but it can take years for proactive care to have an impact. Consider using patient reported outcomes or functional measures, such as Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). It can be difficult to measure patient reported outcomes in proactive care as the person may not recognise the intervention as proactive care, especially when it is being delivered as part of the MDT. Patient experience measures, such as asking “do you feel better, the same or worse?” are a simple measure of a service which can demonstrate patient perceived value. As outcome measures for proactive care are difficult to implement, process measures may provide another approach to demonstrate the value of an intervention. There is evidence that elements of proactive care work, so potential proxy measures may include the number of MDT meetings, CGAs completed, medication reviews undertaken, referrals to strength and balance classes, and advance care plans completed.

Set realistic expectations

It is important to set realistic expectations when developing the service. It can take time to set up a service and tailor it to the skill set of the team, especially as it requires healthcare professionals to work in a new way across the MDT. People will need time to develop into these roles and there will need to be Co-ordinated efforts to make this work. It will also take time for referrals to build up, and for patients, carers, and referrers to understand the service. If the ambition is to set up a large service, flexibility and tailoring to the local area is vital. Building relationships with the wider MDT may also take time and will depend on the history of the service. For example, where there is not an existing MDT in place or local relationships are poor, the process will be even slower.

Allow the service to develop over time using Quality Improvement methodology

The proactive care team can grow over time according to local need but should stay true to its original values. Use data collected to review the service and improve its offer, using the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle or other quality improvement methods. Gather feedback from all members of the MDT, referrers, patients, carers, and adjust the service based on the feedback. Remember to share your experiences with other proactive care services and those wishing to set up their own services.

Develop relationships and governance structures with local services

When developing proactive care services, time should be spent investigating all the services in the area for older people with frailty, including hospital services, community services, primary care, social care, local authority services and voluntary organisations. It is important that connections are made between organisations at the start of the service. This may take time, particularly if there is no well-established multidisciplinary team in place locally. Of particular importance is building strong links with broader community-based services, such as community falls services, urgent community response services, Hospital at Home, community nursing teams and community hospitals. Ensure that clear referral pathways are developed, alongside open routes of communication. Encourage team members to get to know people in other services, so they can phone other health and care professionals rather than making a referral, which enables learning and knowledge exchange. Working closely with other organisations involves learning a new way of working, which reduces duplication and fragmentation. To ensure effective cross organisational working, leadership and system agreements should be put in place across partner organisations to ensure alignment of service delivery.